The White Family’s Game of Now You See Race, Now You Don’t

I am a white woman born to second generation Americans, whose families were not here during the time of slavery, but who undoubtedly benefited from white privilege nonetheless. Stay with me. (Mentioning white privilege when talking about working class immigrants does not negate the discrimination they dealt with regularly.) I could argue that we didn’t start the fire, but our silence as the fire burned is complicity. White people will not do better until we acknowledge the context for that silence and fully understand how it is no longer serving us today. This is not about justifying our actions, rather putting together the puzzle pieces to understand our lives today and how we can do better going forward.

My great-grandparents didn’t pass down their ancestral languages to their kids, and generally didn’t want to do anything that might identify them as immigrants. The goal was to assimilate to American culture, to leave all else behind in pursuit of the freedom this country had to offer. It was by not rocking the boat, even when they were the butt of the abuse, that they were able to achieve some measure of success and then hand it down for me to enjoy today. Which, of course, I feel conflicted about. No, my great-grandparents didn’t always model how to stand up to racial injustice, and this was in part because it paled to atrocities they’d witnessed in their countries of origin and in war. It was also because life is a game of risk and reward. What short and long term consequences will my family suffer if I speak up? They had tackled incredible obstacles to make the smallest of gains, while just trying to keep their children fed (often while losing some of them to illness along the way). To this day, a person will not be concerned with their neighbor when they can’t even secure the lowest tiers of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs themselves (and for an entire family, to boot).

These lessons are consciously and subconsciously handed down. We need to learn from our elders to honor all they sacrificed for us, while at the same time, we need to adapt the messages and lessons for our daily lives. We don’t need many of the survival tactics that got them by, for example. And we can also see when they made a wrong turn or a fear-based decision that was unnecessary at best and harmful at worst.

My mother brought me up decades after the Civil Rights movement. She was an outspoken champion for the underdog and a frequent protester, seeing injustices at every turn, but matters of race were not included in this. Sure, she wanted peace and harmony, and she verbally taught me to “not see race,” which we now understand to be flawed. There were, however, clear lines drawn in the sand when it came to seeing some people as the other. Having once been scolded as a child for drinking out of the “colored” water fountain, she knew that treating black people differently from white people was wrong, but at the same time, she let negative experiences shape her views. Instead of recognizing the systemic issues that put a wedge between her and the black people she served during her time as a Sheriff’s Deputy in a small Southern town, she let contentious encounters inform her opinions about an entire race. In an effort to protect her children, she then taught us what she thought we needed to know about each type of human (each race, each sexual orientation, each gender, and on and on). But parents sometimes forget that kids are also informed by teachers, friends, religious leaders, media, and maybe most importantly, by watching how our parents actually act versus what they say. Words are powerful, there’s no doubt about it, but I grew up watching my family befriend people of all colors, shapes and sizes. The lesson really was that no one was immune from being talked about behind closed doors (myself included), but around our table all were welcomed. I understand today that while breaking bread with people who are different from me is a great start, it doesn’t end there. I can’t say, “I’m not racist because I have a black friend,” and call it a day. I share this because from what I observe, my family was not unique; most white families from this generation operated the same way.

Maybe your white ancestors actually did own slaves and/or maybe some of your current family members are overtly racist. Whatever your story is, you can take the time to understand why beliefs unfolded the way they did and then question them. Just ask yourself: why do we believe what we believe, and with each answer, ask another why. Get to the root of it and see if that is still the truth today (or if it ever was). If you are religious, you have an obligation to compare the racist messaging you have learned with the holy texts you feel loyal to. Are the two aligned?

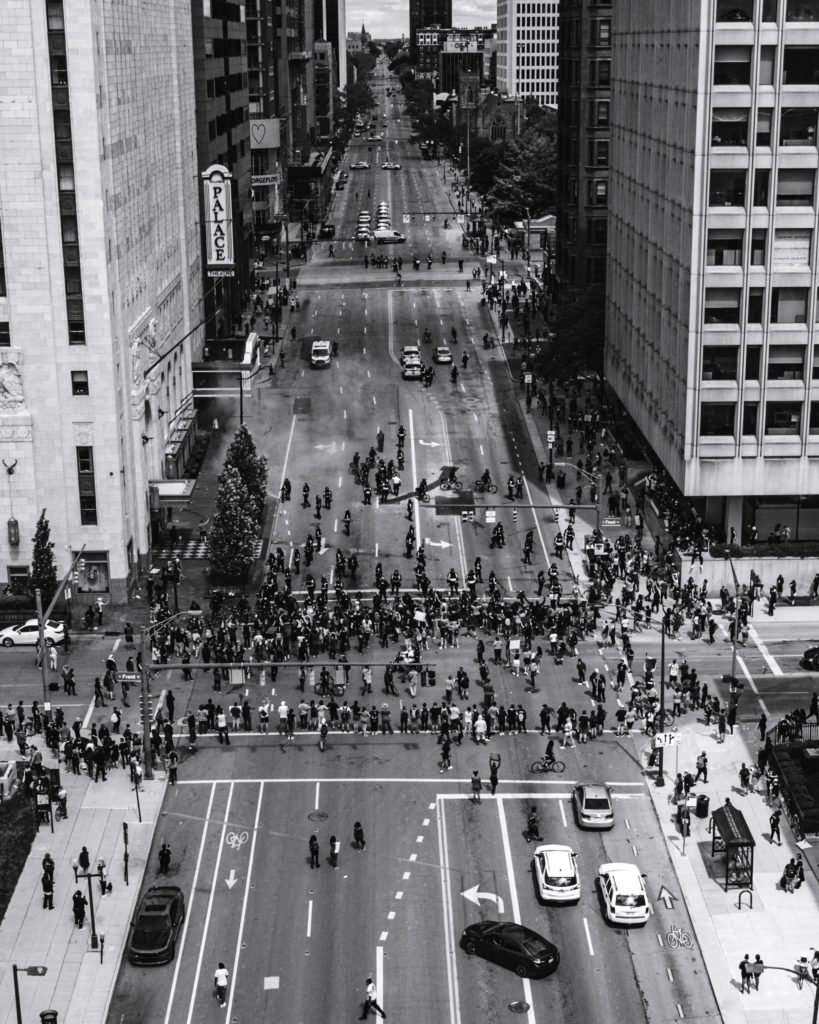

Listen, I’m not trying to shame anyone, nor make excuses for them. I have made plenty of truly embarrassing mistakes myself, and am learning more and more every day. If you see your family in what I’ve written, the point of this is to say you can now zoom out and see the whole picture. The one where we start making progress in our own homes (rethinking racial stereotypes and actually studying white privilege—if you balk at that, start by studying white fragility), as well as affecting change in black communities by fighting voter suppression, supporting black-owned businesses, and making sure black public schools have the same funding as white public schools just to name a few things.

Retrace your family’s intentional or unintentional role in all of this ( it’s never too late) and make one declaration: It ends right now with me.

Additional suggested reading: